(213) 290-6139|bcc@bcc-la.org

(213) 290-6139|bcc@bcc-la.org

This history of BCC was compiled initially for the congregation’s 40th anniversary in 2012 and was revised and updated for the 50th anniversary in 2022. The first two parts are based substantially on the account expertly compiled and eloquently written by BCC history maven Stephen Sass for the 30th anniversary in 2002. Subsequent parts rely on past issues of the BCC newsletter G’vanim and archival materials provided by Stan Notkin and Dr. Mark Katz. Rabbi Lisa Edwards, Tracy Moore, Stan Notkin, Stephen Sass, and Gloria Bitting provided many helpful comments, suggestions, and corrections. Z”l = Zichronam livrachah, may their memories be for a blessing. – Larry Nathenson

BCC is one of many archival collections at ONE Archives at the USC Libraries, available online.

The Founding. On April 4, 1972, four Jews attended a weekly rap group at Metropolitan Community Church in Los Angeles. In less than four years since its founding in 1968, MCC, the first church with an outreach to gays and lesbians, had grown to 15,000 members in 40 U.S. cities. In Los Angeles the “mother church,” led by Rev. Troy Perry and located near USC, had 725 members. The presence of Jews at the church was understandable. In 1972 the existence of lesbian and gay Jews was virtually unheard of. It was a time when same-sex activity was illegal, homosexuality was still classified as a mental illness, and to be openly gay or lesbian usually meant loss of employment and rejection by family and Jewish community. The Stonewall Riots in New York’s Greenwich Village, often considered the watershed event in the modern gay liberation movement, had occurred less than three years earlier.

Those present that evening were Jerry Small z”l, Jerry Gordon z”l, Selma Kay z”l, and Bob Zalkin. When Small expressed unhappiness with a church policy, he was asked why he didn’t simply object, and he said he wasn’t a church member. They quickly discovered none of them were members because all were Jewish. “We could not vote unless we accepted Christ—and that wasn’t going to happen. Then someone said maybe we should form a gay temple.” They then set out to translate their unprecedented vision into reality. They dared to dream of creating a safe place where they could affirm and integrate their identities as lesbians, gay men and Jews.

They turned to Rev. Perry, who hosted a meeting in his office that included Sherry Sokoloff z”l, her partner Gloria Bitting, Jerry Small, Selma Kay and her partner, and Tom Johnson. Rev. Perry agreed they should have their own congregation and offered the use of the church’s facilities free of charge. (The favor would be returned by BCC many years later when MCC’s home was damaged in the 1994 Northridge Earthquake.) As Rev. Perry recalled 25 years later, “Obviously, I’m not Jewish, and I didn’t know much about Judaism or starting a synagogue, but I told them, ‘No matter what you do, make sure you make it really Jewish.’”

About a dozen women and men responded to the call to an ad hoc committee meeting on May 9, 1972, to discuss what was to become the world’s first synagogue founded by and for lesbians and gay men. Among the decisions made at that May meeting: that “Metropolitan Community Temple” would be the name of the group; that “there be a Reform Service for Friday Night Services”; and that announcements of the service would be made by Rev. Perry at MCC services and placed in The Advocate, then a local monthly newspaper in the Los Angeles area. The ad hoc committee also heard a report of Small’s meeting with Rabbi Arnold Kaiman z”l, of the Union of American Hebrew Congregations (now Union for Reform Judaism). Though the Reform movement was the only branch of Judaism expected to be willing to assist such a group, Small went to the meeting with Rabbi Kaiman expecting to have to put up a fight. Instead, Rabbi Kaiman’s only question was, “How can we help you?”

During the organizational meetings that followed, the new congregation began to form committees to draw up bylaws, establish membership criteria and a dues policy, and organize religious services and social events. It was decided that no dues would be charged to members; instead a hat would be passed during services to collect funds. Sokoloff and Bitting formed an oneg committee to organize refreshments after Friday evening services.

The First Services. Fifteen people came to the first service, held June 9, 1972 in Gordon’s home. The following month, a special interfaith service was held at MCC’s sanctuary, to introduce the new temple to the gay and lesbian community. Thereafter, weekly Friday night services were held at MCC, created and led by temple members, with guest rabbis officiating on occasion. From the beginning, MCT’s liturgy reflected the “creative services” then being introduced in Reform and some Conservative congregations, and included the original contributions of members, in addition to selections from the Union Prayer Book and other siddurim. A Basic Judaism class was also necessary, observed Lorena Wellington z”l, since: “[M] any of us had not reviewed our history and what it meant to be a Jew for a long time. Many of us had no formal Jewish education at all. We just knew that we were Jews and wanted to study and learn more about our religion and our heritage.” A formal “Basic Judaism” course taught by Rabbi Allen Secher, UAHC’s Director of Education, began in March 1973.

Rabbi Erwin L. Herman z”l, then director of the UAHC’s Pacific Southwest Council and national director of regional activities, began enthusiastically assisting the fledgling congregation, helping develop lay-led services and adult education classes, obtaining speakers, and lending prayer books, a Torah, and other ritual objects. “Rabbi Herman became our champion…he was our advisor, our friend and mentor. I can’t begin to thank him for all of his work on our behalf,” Wellington wrote in a contemporaneous account. Norman Eichberg z”l, then president of the Pacific Southwest Council, was also a leading supporter. (Sadly, years later, the Herman and Eichberg families would lose sons Jeff z”l, and Rob, z”l, to AIDS.)

By the 1972 (5733) High Holy Days, MCT had 30 members, with twice and sometimes three times that many attending Friday night services. The flyer announcing High Holy Day services noted that “Metropolitan Community Temple was formed to serve the spiritual needs of the Homophile Jewish Community—the first of its kind in America.” [Actually, in the world.] Though most weekly services were lay-led, the members wanted a rabbi for High Holy Days. Rabbi Herman later wrote: “Our attempts to fill the pulpit met only with disappointment. Some colleagues to whom we turned were otherwise occupied or traveling elsewhere. Some others, however, available for High Holyday placement, noted candidly that the distance between ‘Rabbi of the Homosexual Temple’ and ‘Homosexual Rabbi of the Temple’ was too slim to permit their participation.” As a result, the members conducted High Holy Day services themselves, assisted by a straight woman educator who acted as cantor, Mary Anne Freiheiter, better known later as Aviva Kadosh [a longtime consultant for L.A.’s Builders of Jewish Education]. The following year, Rabbi Richard Sternberger z”l, then UAHC director in Washington, D.C., traveled to L.A. to lead BCC services for free.

The drafting of bylaws and membership criteria proved to be a challenge, as the members disagreed about whether membership should be open to non-Jews. Small and Kay, who had been serving as co-chairs of the steering committee, disagreed on a path forward and resigned their positions. Sokoloff was elected interim president and helped to guide the congregation through this and other important decisions in the final months of 1972.

Choosing a Name, and the Great Fire. After services at MCC on Friday evening, January 26, 1973, the synagogue passed its first bylaws and held its first election of officers, selecting Stuart A. Zinn z”l, as the first president. To distinguish the synagogue from MCC, the members also chose a new Hebrew name that night from suggestions written on pieces of paper. The proposed names included “Children of Pride-Yeladim Shel Gaavah”; “The House of the Children of Peace – Beth Yeladim Sholom”; “The House of the Children of Unity—Beth Ylodim Shel Achdus”; “The House of Eternal Truth—Beth Tamid Emet”; “The House of Eternal Life—Beth Ha Chayim”; Temple Emanuel, and “Congregation Beth Ahavah—The House of Love.” Small, one of the first four founders and the congregation’s newly elected vice president, submitted the winning entry. Inspired by New Life, the name of Metropolitan Community Church’s newsletter, Small asked a friend to translate “House of New Life” into Hebrew, which was rendered as “Beth Chayim Chadash” and which won by a vote of 26-0. Subsequently, Rabbis Herman and Ragins pointed out that “Chadash” was grammatically incorrect and so the name was changed to Beth Chayim Chadashim.

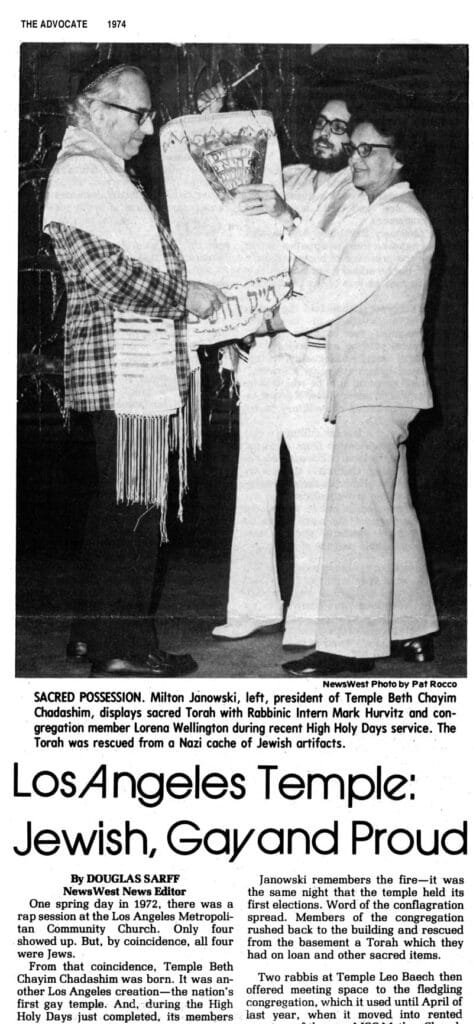

After the meeting that Friday evening, some members adjourned to Canter’s Delicatessen on Fairfax Avenue. Shortly after midnight, Milt Jinowsky z”l a board member and ritual committee chair, was on his way home and heard on the radio that the MCC building was on fire. He rushed to a phone, called Canter’s and told Zinn the terrible news. Wellington recorded the dramatic scene: “With one accord, the entire group of us, about 20 or so persons, left in our cars. We raced to the scene of the fire. There we surrounded the Fire Chief. ‘Our Torah is in that building—we have to get it out.’ We all shouted at him. The Fire Chief, overwhelmed by the sheer number of us and our almost hysterical insistence, finally asked us to select one member to go into the burning building with him. “Unanimously we turned to our new president-elect, Stu. His first act as President was to enter the burning building with the Fire Chief and rescue our Torah [on loan from the UAHC]. He was gone such a long time, more fire trucks arrived, the flames shot skyward as the spire burned more fiercely, the firemen were pushing us back to the sidewalk—‘Where is he?’ we asked each other. ‘Has Stu come out yet?’ Then, out of the smoke, with his pants legs rolled up—came Stu— tenderly carrying our Torah in his arms! We all broke into tears!

L.A. Times photo of MCC fire, January 28, 1973

“Our Torah was water damaged, but safe. That night, we spent the entire night tenderly unrolling our Torah, both men and women, reverently weighing down the wet corners so that it might dry. Both men and women spent the night on their knees—thanking God silently for our Torah and carefully putting books, papers and weights wrapped in wax paper on the curling sheepskin. Our togetherness was never closer than at that moment…” While the Torah was rescued (although another account said that in spite of these efforts, it was later decided that the scroll was damaged beyond repair and had to be buried), the MCC building sustained $160,000 in damage, was deemed a total loss and ultimately torn down. Although the fire was initially determined to be of suspicious origin, arson was later ruled out by the Fire Department, but doubts as to the cause persist to this day.

Help from Leo Baeck Temple, and our Survivor Torah. Until MCC could be rebuilt or relocated, BCC needed to find a new place to meet. It didn’t have to search long. Rabbis Leonard Beerman z”l and Sanford Ragins of Leo Baeck Temple came forward, contacting the congregation and volunteering the use of the Temple’s classroom building for Friday evening services. The rabbis also said they would address any issues that might arise with their temple’s board (none did) and thanked BCC for the opportunity to perform a mitzvah.

On March 3, 1973, some 400 people, including city officials and leaders of the Jewish and gay communities, gathered at Leo Baeck to dedicate a new Torah for BCC. Participants included the officers of the congregation, Rev. Perry, Rabbi Herman, Rabbi Ragins, Dr. Lewis M. Barth, dean of Hebrew Union College’s California School and Cantor Dora Krakower z”l, one of Reform Judaism’s pioneer woman cantors. (The first woman rabbi, Sally Priesand, was ordained by HUC in 1972.) Unfortunately, the Torah’s donor was anonymous and not among the celebrants, for as Rabbi Herman indicated: “As a practicing professional in a neighborhood contiguous to Leo Baeck, he lived his life publicly as a ‘straight.’ Had he made public acknowledgement of his homosexuality, he feared the social stigma and economic repercussions that often accompany such knowledge.”

The Torah itself had an unusual story. It was Czech Scroll #115, from the town of Chotebor, written in 1880 and one of 1,564 Torah scrolls found in Czechoslovakia after World War II, representing hundreds of Jewish communities in Bohemia and Moravia that had been destroyed in the Holocaust. The scroll was part of a huge collection of Jewish ceremonial objects that the Nazis had confiscated and desecrated but saved for a permanent exhibit of “relics of the extinct Jewish race,” which they planned to set up following the victory of the so-called Thousand-Year Reich. The Torah scrolls were later rescued by Ralph Yablon z”l, an English solicitor and philanthropist who contributed them to the Westminster Synagogue in London, which restored and made them available on permanent loan to Jewish communities around the world. This Torah remains one of BCC’s most cherished possessions to this day.

After an eventful first year punctuated by the great fire at the Metropolitan Community Church where the fledgling congregation had met, and by the dedication of our Holocaust survivor Torah, BCC began a decade of growth and of finding its way into the mainstream of Jewish life in Los Angeles, the Reform Movement, and the emerging world community of LGBT Jews.

A Pioneer in Egalitarian Worship. By its second year BCC was experiencing growing pains. Rabbi Herman, a strong supporter of BCC, wrote: “Tensions sprang up within the group, which soon found itself divided on issues of traditionalism vs. nontraditionalism, acceptance or rejection of non-Jews into membership, rigid vs. fluid constitution, etc…” The “etc.” included such issues as ongoing conflicts between the congregation’s men and women (of the 60 members, less than half were women), and whether or not to accept heterosexuals as members (the few heterosexuals who did join BCC then were relatives of gay members, such as Jerry Gordon’s parents, Al and Lorraine).

Despite or perhaps because of such struggles, BCC was a pioneering congregation in egalitarian worship with lay service leaders and in the creation of life cycle rituals for lesbian and gay individuals and couples. And at a time when most temples (including Reform ones) still used male language for God, BCC created the first prayer book with degenderized language. Harriet Perl z”l, convinced the male BCC leadership in the mid 1970s that this step would make lesbians more likely to join and would make them feel equally a part of the congregation in all respects. She made her proposal to President Milt Jinowsky, who could have simply dismissed her because she wasn’t yet a member, but instead he asked if she would like to take on the project, and Jesse Jacobs z”l, volunteered to assist. Given the nation’s growing awareness of women’s rights, their gender-egalitarian prayers soon made their way into siddurim across the country.

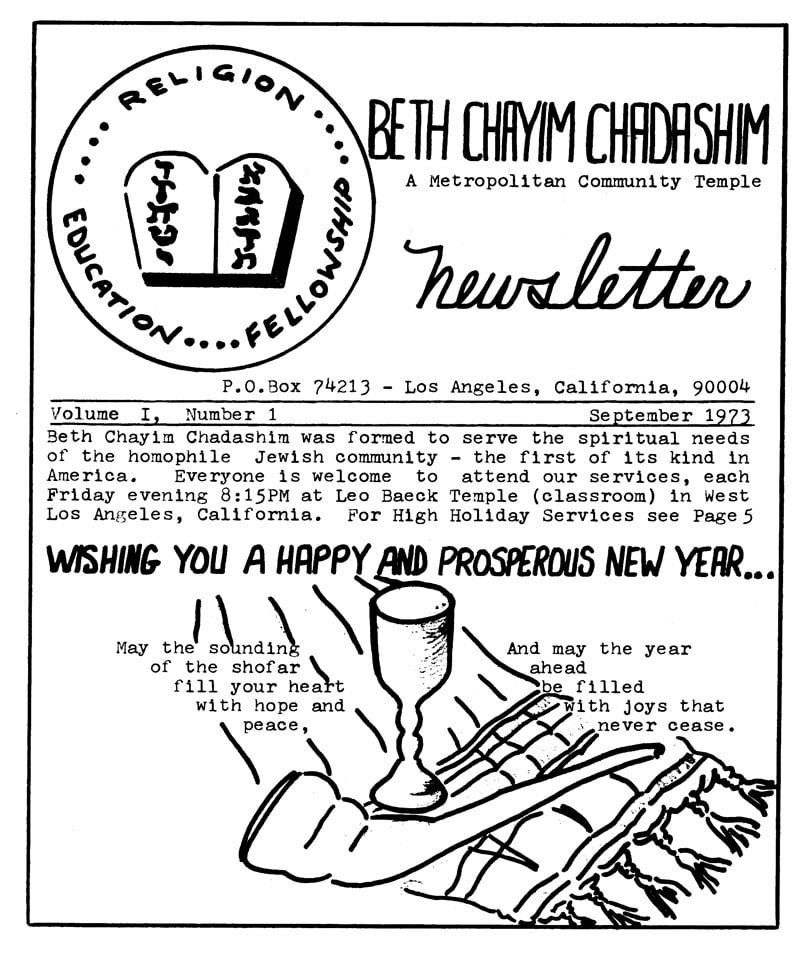

Cover of the first BCC newsletter, September 1973

In September 1973, Sokoloff and Bitting produced BCC’s first monthly newsletter. Making use of Sokoloff’s artistic skills, the cover included a logo representing the three traditional functions of the synagogue (religious services, education, and fellowship or assembly) and also included ritual objects representing the High Holy Days. By 1976 the logo was a circle containing both a Star of David and a Greek letter lambda, reflecting the Jewish and gay/lesbian character of BCC. At first it was simply called the BCC Newsletter; the name G’vanim (Hebrew for “colors” or “hues”) was chosen in 1980, most likely a reference to the rainbow flag symbol of the gay and lesbian community. For some 30 years, until the widespread use of email and the internet, the monthly newsletter served an important function as BCC’s principal means of communicating with members and other interested persons about upcoming events and congregational matters.

Engaging with the Los Angeles Jewish Community. During these early years, BCC engaged with the wider Jewish community in L.A. and became an organizational member of the Jewish Federation Council of Greater Los Angeles. When the now defunct B’nai B’rith Messenger, then L.A.’s most widely read Jewish newspaper, editorialized against BCC and the Federation, congregations and individuals from around the Southland were quick to denounce the Messenger’s bigotry.

One of BCC’s earliest projects was at the Israel Levin Center in Venice (now known as BAR Center at the Beach). As Jerry Nodiff recalled in G’vanim: “This was (and is) a Jewish community center focused on meeting the needs of Jewish seniors. In the 70s the center was having a challenging time meeting the food needs of its seniors, and a produce oneg Shabbat was created to give them produce items to tide them over the weekend. BCC was one of a number of temples supporting the program, and found money in a modest temple budget to support it for several years. In 1977 and 1978 BCC sponsored benefit concerts, ‘In Celebration,’ at Leo Baeck Temple to raise money for supplemental programming for the seniors. The concerts were magical evenings and novel in the sense that they were a mix of cantorial music, Israeli dance, and other forms of entertainment. While both concerts were successful, the first one sold 600 tickets, a sell-out.”

Project Caring was another BCC social action venture that began in the 1970s, and it continued for more than three decades. One Shabbat morning each month, a group of BCC members brought a Shabbat service to residents of Country Villa Wilshire convalescent home, along with a large dose of music and friendship. Our beloved Sue Terry z”l, who participated in this mitzvah throughout BCC’s involvement, later became a resident in a convalescent home herself.

Joining the UAHC. During its second year, BCC applied for membership in the Union of American Hebrew Congregations (now Union for Reform Judaism), sparking wide debate within Reform Judaism and beyond. Upon receiving BCC’s application for membership, Rabbi Alexander Schindler z”l, then UAHC president, engaged in a time-honored Jewish tradition: he posed the following question to a group of rabbis and others, to hear their answers (known as “responsa”) and to make a decision based on informed, deliberative opinion: “A rabbi on the West Coast [Rabbi Herman] has organized a congregation of homosexuals. He has said: ‘These are people facing their own situation. They have become a social grouping.’ Is it in accordance with the spirit of Jewish tradition to encourage the establishment of a congregation of homosexuals?” Seven responsa were written, five by rabbis (two opposed to BCC’s admission, three in support) and two by psychiatrists (the supportive one written by Dr. Judd Marmor of USC).

Rabbis Beerman, Herman and Ragins each submitted passionate responsa in support of BCC’s application. Rabbi Herman wrote about his and the Pacific Southwest Council’s support of the congregation: “We responded by offering the facilities of our office for the formation of their synagogue, as we have done in the past and will continue to do in the future to any group of Jews who demonstrate to our satisfaction that they are sincerely interested in the creation of a synagogue.” Rabbi Ragins, after movingly describing BCC and the congregation’s Torah dedication at Leo Baeck Temple, wrote: “…And what then of this Metropolitan Community Temple, this Beth Chayim Chadashim established to reach out to Jewish homosexuals? Is its existence justified? Should it receive our support and cooperation? Again, I believe the answer is clear. In principle, such a synagogue should not exist, because all synagogues should be so open that all Jews may feel fully welcome and at home in them. But clearly, this is not the way our world or our family-oriented congregations are constituted today. Until the temples we already have are able to accept Jewish homosexuals in their homosexuality, as they are and not as we would want them to be, homosexuals who want their own congregations should not only be allowed to have them, but encouraged and assisted, and accorded full membership in the UAHC. To do anything else would make us accomplices of the repressive patterns of our culture, patterns that should be broken and discarded on the junkheap of civilization.”

Rabbi Solomon A. Freehof z”l, a professor at Hebrew Union College, a highly respected scholar, and the most prolific author of Reform responsa, was unalterably opposed to a separate congregation for gay and lesbian Jews and to its admission to the Union: “There is no question that the Bible considers homosexuality to be a grave sin. The rabbi who organized this congregation said, in justifying himself, that being Reform, we are not bound by the halachah of the Bible. It well may be that we do not consider ourselves bound by all the ritual and ceremonial laws of Scriptures but we certainly revere the ethical attitudes and judgments of the Bible… Opposition to homosexuality was more than a biblical law; it was a deep-rooted way of life of the Jewish people. Therefore homosexual acts cannot be brushed aside by saying that we do not follow biblical laws. Homosexuality runs counter to the principles of Jewish life; from the point of view of Judaism, people who practice homosexuality are to be deemed sinners… Does it mean therefore, that we should exclude them from the congregation and compel them to form their own religious fellowship in congregations of their own? No! The very contrary is true. It is forbidden to exclude them into a separate congregation. As Jews, we must pray side by side with the sinners….

“They are excluding themselves; and it is our duty to ask, why are they doing it? Why do they want to commit the further sin of ‘separating themselves from the congregation’? Part of their wish is, of course, due to the ‘Gay Liberation’ movement. Homosexuals, fighting the laws which they deem unjust, take a strong stand in behalf of their status to gain formal recognition from all possible groups. If they can get the Union of American Hebrew Congregations to acknowledge their right to form separate congregations, it will bolster their claim for other rights. It seems to me, also, that it is not unfair to add another motive for their desire to be in one congregation: in this way they know each other and are available to each other, just as they now meet in separate bars in the large cities. What, then, of young boys who perhaps have only a partial homosexual tendency, who will now be available to these homosexuals? Are we not thereby committing the sin of ‘aiding and abetting sinners’? To sum up: Homosexuality is deemed in Jewish tradition to be a sin, not only in law but in Jewish life practice. Nevertheless, it would be in direct contravention to Jewish law to keep sinners out of the congregation. To isolate them into a separate congregation and thus increase their mutual availability is certainly wrong.”

Dan Hansman, a long-time BCC member, wrote in a 1975 Davka article entitled “The Gay Jew: An Alternative” that after BCC’s leaders steered through “the complex maze of surprise, resistance, ignorance, prejudice, love and goodwill,” the UAHC’s national board overwhelmingly approved BCC’s membership on June 9, 1974, the last step of a four-stage regional and national process. The UAHC charter was presented at BCC’s second anniversary service the following month. BCC’s admission to the UAHC marked the first time a synagogue with an outreach to gays and lesbians was accepted by any of the Jewish movements. It was also the first gay and lesbian congregation of any faith accepted into membership by a mainstream religious denomination.

Helping Found the World Congress. While it was finding its way into the Jewish mainstream, BCC had received inquiries from gay and lesbian Jews from throughout the United States, as well as Israel, England, and other countries, interested in starting their own congregations and organizations. A group in London had formed in 1972, and several synagogues in other U.S. cities formed in the next few years. In 1976, in Washington, D.C., representatives of BCC and several other organizations attended the First International Conference of Gay Jews (“Lesbian” was added in 1978 on a motion by our own Harriet Perl). In 1980 in San Francisco, the World Congress of Gay and Lesbian Jewish Organizations was officially born. Since then it has changed its name several times, and is now known as the World Congress of GLBT Jews: Keshet Ga’avah (the Hebrew name means “rainbow of pride” and reflects the importance of Israel to the organization). Over the years, the World Congress has expanded to include synagogues, community groups, social service and advocacy organizations in the U.S. and Canada, Latin America, Europe, Israel, and Australia.

BCC hosted conferences of the World Congress in 1978 and 1982, co-hosted one in 2010 at UCLA Hillel, and has also hosted World Congress board meetings and several Western Regional Conferences over the years. Stan Notkin and later Jonathan Falk have served tirelessly as BCC’s representatives to the World Congress for most of the past 35 years.

This Vagabond Shul Finds a Home. After the great fire of January 1973 forced BCC from its first meeting place at MCC, Leo Baeck Temple hosted BCC for 14 months. BCC then decided to move to MCC’s new home downtown on Hill Street. Two years later (1976) BCC moved once again to the Academy West dance studio on Westwood Blvd., owned by Benn Howard z”l, who served as BCC’s president during 1977-79.

In 1977, after meeting in its several temporary homes, BCC purchased the property at 6000 W. Pico Blvd. for $86,000, the first gay and lesbian synagogue to buy its own building. The inaugural service took place on November 11 that year. But the building still needed extensive renovations, and those who were members at the time recall black drapes covering the walls, construction lights with cables strung from one to the other, and folding ladders to sit on during services. The remodeling was completed in 1980, and the building was dedicated in 1981. Thanks to a very generous donor, the congregation burned its mortgage in 1983.

At the end of its first decade, BCC had many accomplishments under its belt. The fledgling temple had become a pioneer in egalitarian liturgy, had been admitted to the Union of American Hebrew Congregations, helped found the World Congress of Gay and Lesbian Jewish Organizations, and bought the building at 6000 W. Pico Blvd. that would serve as its home until 2011. In its second decade BCC matured as a congregation in a number of ways, some by choice (paid clergy, annual awards), and some forced upon it (the need to respond to the AIDS epidemic).

Our First Ordained Clergy. In 1983 the Board of Directors decided to engage BCC’s first ordained rabbi, though only on a part-time basis. This choice was not welcomed by all of the members. In its first decade BCC had maintained an ethos of close-knit community and “do it yourself” Judaism, with mostly lay-led services and no paid clergy or staff. Several rabbinic students at Hebrew Union College had served BCC as rabbinic interns, including Scott Sperling, Mark Hurvitz, Keith Stern, Leah Kroll, and Margaret Holub. But some members felt that professional clergy would detract from the spirit of the congregation and encourage members to become a passive audience during services. The hiring of a part-time office assistant gave rise to similar reservations.

Despite these doubts, the Board made an inspired choice in Rabbi Janet Ross Marder. A heterosexual woman, pregnant with her first child, Rabbi Marder had no particular interest in gay and lesbian issues when she applied for the position. But she soon became a highly effective ambassador for BCC. She organized meetings and dialogues with mainstream congregations, so that their rabbis and members could get to know GLBT Jews and learn to understand and respect our relationships and our spirituality. She became a strong advocate for LGBT rights in the wider Jewish community as well. Even after she left BCC, a “speakers bureau” continued dialogue and outreach to mainstream temples.

Within BCC, Rabbi Marder won the respect and admiration of BCC members for her quiet, self-effacing manner combined with a strong intellect and a deep caring for both Jewish tradition and the needs of her congregants. She encouraged adult learning within BCC, teaching several courses during her five years as our rabbi. She also helped start the Cele Bernstein Library (named for an early BCC member who passed away in the late 1980s), which functioned for a time as a lending library in the same room that served as the rabbi’s office.

There were several ritual “firsts” during the 1980s, including the congregation’s first bat mitzvah, Gloria Bitting, on April 16, 1983, and the inauguration of lay-led services on Second Day Rosh Hashanah. Rabbi Marder worked with the Ritual Committee to develop a revised Shabbat evening prayer book with even more gender-neutral language and original prayers and poems unique to our community. BCC also acquired and dedicated a second Torah scroll to supplement our beloved Czech survivor Torah.

Another highlight of Rabbi Marder’s tenure was the “simchat chochmah” (celebration of wisdom) of Savina Teubal z”l, held at BCC in 1986. A noted Jewish feminist scholar and author of Sarah the Priestess, Savina created this new liturgy for her 60th birthday. The ceremony introduced the now well-known song “Lechi Lach,” composed by Savina and Debbie Friedman z”l, a talented composer and singer who helped to revitalize Jewish music in the last two decades of the 20th century.

Though she was warned that accepting the position with BCC would jeopardize her future, it was in fact a boost for Rabbi Marder’s career. After leaving BCC in 1988 she became assistant director and then director of the Pacific Southwest Region of the UAHC, the first woman president of PARR (Pacific Association of Reform Rabbis) and of CCAR (Central Conference of American Rabbis), and served as senior rabbi of Congregation Beth Am, a major Reform temple in the San Francisco Bay Area, from 1999 until her retirement in 2020.

In 1986 BCC engaged its first long-term invested cantor, Don Alan Croll, after several years of cantorial services by such talented individuals as Elliott Pilshaw, Lorin Sklamberg, Mark Saltzman, and Robin Taback Ariel z”l. Cantor Croll introduced new music to BCC, adding many classical Reform melodies as well as more traditional ones, and founded BCC’s first choir. Cantor Croll served BCC until 1992, after which he too went on to a successful career.

The Herman Humanitarian Award. In 1985 BCC established its first major annual award, named in honor of Rabbi Erwin Herman and his wife Agnes z”l to recognize individuals and organizations for their outstanding contributions to the LGBT and Jewish communities. The choice of name was obvious, as Rabbi Herman had been a stalwart champion and dear friend of BCC in its early years and especially in its application to join the UAHC. He had also helped BCC secure student rabbis from HUC and assisted in developing its liturgy. Agnes Herman was also a strong advocate for BCC in the Jewish community as well as a tireless educator and advocate on LGBT and HIV/AIDS issues.

Shortly before his death in 2008, Rabbi Herman said “If in my rabbinate, which now numbers 58 years, I have accomplished nothing else, the experience of being part of Congregation Beth Chayim Chadashim, in its birth and its constantly maturing development, is my ‘dayenu’.”

The Onset of the AIDS Epidemic. BCC was also forced to mature in the 1980s by other less fortunate circumstances. The euphoria of the first decade of gay liberation after Stonewall, and after the founding of BCC, came crashing to a halt. As BCC member Dr. Mark Katz reminded us in November 2011 on the occasion of 30 years of the AIDS epidemic, “the first cases of gay men dying from immune system disorders were published on June 5, 1981. In cities such as Los Angeles, however, health care providers had already seen, in the prior one to two years, some cases of gay men becoming ill with unusual infections.

“The medical community did not know why these cases of Pneumocystis pneumonia or Kaposi’s sarcoma were cropping up, but as they were ascribed to the gay community, the acronym GRID (Gay-Related Immunodeficiency) was born. It wasn’t until more than a year later, on September 24, 1982, that the term Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome was coined by the Centers for Disease Control. Los Angeles, one of the three major epicenters in the U.S., was thrown into a maelstrom, first by not knowing what caused it (poppers? stress? parasites?), and ultimately, by the lack of effective treatments … Funerals and memorial services became as commonplace as parties used to be; most of us who were alive at the time recall the unbelievable experience of leaving one memorial service early so as to attend another one.”

The U.S. government under President Reagan (who famously did not utter the word “AIDS” until nearly the end of his term in 1987) did little to address the epidemic, leaving the gay community to fend for itself. As Dr. Katz recalled, “the gay community—female and male—rose to support each other, in a way I predict will forever be inscribed in the history books. Through our tragic losses, we created the richest, deepest sense of togetherness imaginable.” The tensions between lesbians and gay men that had characterized the first decade of gay liberation (and of BCC) lessened dramatically. A number of physicians (including Dr. Katz) became activists to advocate for research and treatment while desperately trying to save their patients’ lives. The spiritual and social services communities also came through, offering everything from spiritual retreats, support groups, and free psychotherapy to food pantries and free health care.

In 1987 BCC rose to the occasion and inaugurated its monthly PWA dinners, bringing Persons with AIDS and their partners together with BCC members and clergy for a free meal with conversation and support. A number of BCC members also participated in SHALOM brunches (Synagogue Hospital AIDS Loving Outreach Meals). These programs continued for several years until new medications made AIDS a more manageable chronic disease. The spirit of connecting through meals also carried over into other social action programs, including monthly dinners that BCC sponsored and cooked for residents of Turning Point, a shelter for homeless individuals in Santa Monica.

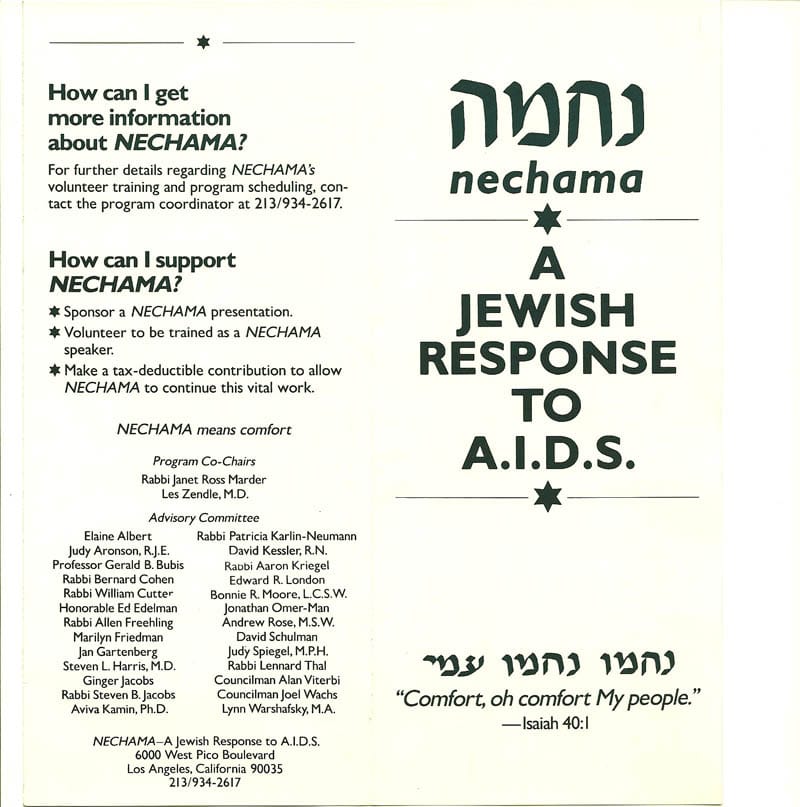

Nechama: A Jewish Response to AIDS. BCC also sought to engage the wider Jewish community in responding to the crisis. With a $13,800 grant from the Jewish Federation’s Council on Jewish Life, Rabbi Marder and BCC member Dr. Les Zendle founded Nechama in 1986. Nechama (“Comfort”) sought to educate the Jewish community about the AIDS epidemic by training volunteers to speak to synagogues and other Jewish groups about AIDS from a Jewish perspective. The speakers bureau was very active; an August 1987 report listed 38 completed and 29 upcoming presentations from January 1987 through April 1988. Presentations usually included a short film, discussion of why AIDS is a Jewish issue (the mitzvot of pikuach nefesh or saving life, compassion for the sick, and not allowing individuals to be isolated from the community), up-to-date medical information, discussion of transmission and “safer sex” precautions, pros and cons of the new AIDS test, and ways to help infected persons. Training packets included the latest medical data, newspaper articles, safer sex guidelines, and lists of community resources to enable speakers to answer questions from their audiences.

Nechama brochure, 1987, courtesy of Dr. Mark Katz

A number of BCC members, including Dr. Katz, served on the advisory committee or the speakers bureau. Dr. Katz recalls that the most effective presentations included a person living with AIDS who could make the crisis personal and emotional, along with doctors who could give the medical updates. The most common questions were about methods of transmission, such as whether you could get AIDS by kissing. The angriest response he recalls was from a group of Jewish camp teenagers, who were angry about being robbed of the carefree sex lives they would have had.

Nechama later became part of Jewish Family Service, where BCC members Jerry Small and later Avram Chill z”l, served as its director. Later renamed Los Angeles Jewish AIDS Services, it is known today as Project Chicken Soup, which provides kosher meals twice monthly to persons with HIV/AIDS in the Greater Los Angeles area. Many BCC members have volunteered to cook and deliver food for PCS over the years.

The Impact of AIDS Within BCC. In the meantime, AIDS took a heavy toll on the membership of BCC. The scale of the loss can be seen in our annual Yizkor book, which lists all deceased BCC members on its first few pages in the order of their deaths. During the first decade, 1972-1982, only seven BCC members died. From 1983 to 1994, there were 40 members who died, about two-thirds of them from AIDS. A majority of the members who have passed since 1994 died from other causes and at older ages.

Going to funerals of friends and congregants became a common BCC experience during the 1980s and early 1990s. The fact that so many of the deceased were young, in their 20s, 30s and 40s, made the tragedy all the more painful. Rabbi Denise Eger, who succeeded Rabbi Marder in 1988, founded an HIV Support Group for BCC members. G’vanim ran a column during these years called “Maccabees,” written by a different member of the HIV support group each month, about the challenges of living with HIV. By 1992 the column was no longer being written, and by the summer of 1994 all but two members of the original BCC HIV support group were deceased.

Some BCC members responded to the crisis with poetry. Yaffa Weisman’s “My Future Iyovim” (Job) continues to appear in our annual Yizkor book. Here is part of another poem by then BCC member Ron Koff, entitled “Steadily They Go,” that appeared in the November 1990 issue of G’vanim:

Steadily they go, first one by one,

Then by twos and threes,

Yanked out of our world, now torn asunder,

By the brawny arm of an uncaring, unyielding God.We who remain learn to wall ourselves off from pain

With words of dismay,

Striving to convince ourselves as we retreat into the bright, familiar parts of our lives, that the nightmare isn’t real.We huddle together for warmth and tell each other

It’s only a bad dream.

Toward the end of BCC’s second decade, two passings not from HIV/AIDS shocked the congregation. The first was Vicki Goldish, a highly intelligent and spiritual woman who energized BCC’s community like few others, who died of cancer in her early 40s. The second was Ralph Stevens, also in his 40s, the only BCC president to die while in office. Many BCC members attended a Western Regional Conference of the World Congress in Malibu in March 1992, returning home to discover that Ralph had passed away during the weekend. The funerals of Vicki and Ralph reminded BCC that while you may learn to mourn, you never really get used to it.

As BCC approached its 20th anniversary in 1992, it continued to face the challenges of the AIDS epidemic that had dominated the previous decade in the GLBT community. But internal concerns surrounding BCC’s rabbinic leadership now took center stage.

A Challenging Transition. In late 1991, the Board of Directors voted not to renew Rabbi Denise Eger’s contract for an additional term. This decision was highly controversial and led to a packed congregational meeting early in 1992 at which some members tried unsuccessfully to reverse the Board’s decision. Lisa Edwards, then serving as BCC’s student rabbi, played a central role in that meeting, urging calm and respectful dialogue in the best interest of the temple as a whole.

Membership had swelled during Rabbi Eger’s four-year tenure, approaching 400 members. Most of those who had been members for more than four years remained with BCC, but many of the newer members left to form Congregation Kol Ami, L.A.’s second predominantly LGBT synagogue, which Rabbi Eger has now served for almost 30 years. Those who remained faced a difficult transition but, as always, rose to the occasion. A havdalah celebration for BCC’s 20th anniversary drew some 250 people. And in the first elections for a new Board of Directors, there were more candidates willing to serve than seats open for election, a circumstance that few temples experience and that has not been repeated.

By High Holy Days in 1992 BCC had a new rabbi, Mark Blumenthal z”l, who had previously served as a chaplain in Denver. Rabbi Blumenthal used his skills to help the congregation heal from its recent wounds and begin to move forward once again. As Cantor Don Croll had recently resigned, a guest cantor, Janet Bieber, was engaged for High Holy Day services.

In 1993, Fran Magid Chalin began to serve BCC as cantorial soloist, a position she held until the end of 2007. Fran had been a congregant for several years, and had been instrumental in organizing the PWA (Persons with AIDS) dinners during the late 1980s. Though not an invested cantor, her musical skill and her haimish spirituality endeared her to the congregation from the start. In addition to leading Shabbat and holiday services, Fran continued to direct the BCC choir and, in 1996, helped start the “Gay Gezunt” klezmer band.

As a parent in an opposite-sex relationship, Fran also played a central role in expanding BCC’s horizons beyond its adult gay and lesbian roots. Over the years, she helped educate the congregation about bisexuality (the “B” in LGBT) and later about transgender concerns as well. Fran also played a leading role in expanding the services available to families with children at BCC (see below).

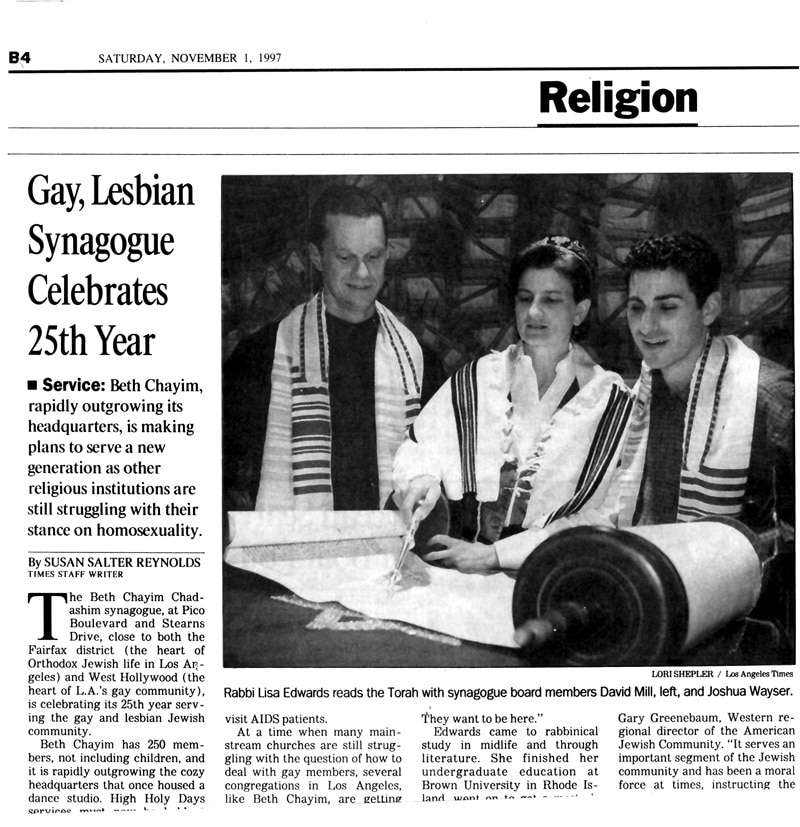

Rabbi Lisa Edwards Joins BCC. In 1994 BCC once again formed a rabbinic search committee, but this time the choice was clear. Newly ordained Rabbi Lisa Edwards had served as BCC’s student rabbi two years earlier, and she and her partner (now wife) Tracy Moore were already known to the congregation. Rabbi Edwards was also BCC’s first rabbi to be openly gay or lesbian at ordination, as the Reform movement’s rabbinic organization (CCAR) had voted to admit openly gay rabbis in 1990.

Rabbi Edwards received a Ph.D. in English Literature from the University of Iowa before beginning her rabbinic studies. Her experience with the small Jewish community in Iowa City helped convince her to become a rabbi. “As a lesbian and a woman, I often felt excluded by a community that was not yet reaching out to Jews with diverse lifestyles and backgrounds,” she wrote in the October 1994 issue of G’vanim. “Among the many reasons I am thrilled to be back at BCC is the congregation’s understanding of difference, alongside its passion for Judaism and for creating Jewish community.”

Rabbi Edwards quickly became a unifying and healing force in the life of BCC. Her warmth and compassion, her keen intellect and well-crafted drashot (sermons), and her deep knowledge of Jewish tradition made her a beloved teacher, counselor, and spiritual leader. She also raised BCC’s profile in the L.A. Jewish and LGBT communities, teaching courses at HUC in the rabbinic program and at USC in Jewish studies. She often wrote for the Jewish Journal and became a sought-after speaker on the intersection of faith, sexuality, and human rights. Her writing also appears in The Women’s Torah Commentary, Lesbian Rabbis: the First Generation, Mentsh: On Being Queer and Jewish, and Torah Queeries. Her wife Tracy Moore is author of the oral history Lesbiot: Israeli Lesbians Talk about Sexuality, Feminism, Judaism and their Lives and served on the board of ONE Archives Foundation.

Under Rabbi Edwards’s leadership, BCC continued its rebuilding and expanded its programming during its third decade. Some highlights of this period were:

Serving All of our Congregants. In its early years BCC was a small and close-knit community, with most of its activities designed for the entire congregation. Although this did help to unify the membership, it also meant that most activities were led by and directed to the majority of members who were adult gay men. In the second decade the AIDS crisis tended to overshadow other congregational needs, though it did rally the membership around a common cause.

As the congregation rebuilt itself during its third decade, a profusion of smaller groups and programs within the congregation emerged to address the needs of specific subgroups. For example, since BCC is not a neighborhood synagogue and draws from all over the L.A. metropolitan area, regional havurot (social groups) were initiated for members living in the Westside, San Fernando Valley, Hollywood/Silver Lake, and other areas. Previously the only recognized havurah was Havurah Aleph, which consisted mostly of older gay men.

BCC also began to acknowledge that its members came from a variety of Jewish backgrounds. In the second decade, with ordained clergy from the Reform movement, the original free-form liturgy shifted toward mainstream Reform. In 1991, members who wanted a more traditional service founded the Traditional Egalitarian Minyan, a lay-led service once a month on a Shabbat morning. Now renamed simply Shabbat Morning Minyan, it features Torah chanting, more extensive liturgy, study and discussion, and a potluck dairy lunch.

The 1990s also saw an upswing in the number of Jews by choice in the BCC community, with specific programming on becoming Jewish and panel discussions by and for Jews by choice. Compared to other temples, BCC has long had a high percentage of Jews by choice in its membership, including three of its past presidents (Tom Johnson, David Mill, and Davi Cheng, who is almost certainly the only Chinese-American lesbian synagogue president ever). Karen Wilson, Arlan Wareham, Tracy Moore and Cecilia Quigley were also among those who embraced the covenant during this time. More recently, under Davi's leadership BCC has forged ties with B'Chol Lashon ("In Every Tongue"), an organization of multicultural Jews from around the world.

Programming specifically for women also increased during BCC’s third decade. Though a BCC Sisterhood began in 1990, social and educational programming specifically for women was expanded under the name Nashim L’Nashim (women for women) in 1994. From women-led services and spiritual retreats to game nights, brunches, pool parties, and feminist discussion groups, BCC began to offer a full range of services to its women members.

In 2002, a Life Transitions Group led by social worker Shirley Hirschberg began to offer a space to share feelings about losses, relationship and career changes, family and health issues in a supportive and confidential atmosphere.

Another major development of BCC’s third decade was the inauguration of children’s programming under the name Yeladim B’Lev (children in the heart). Several BCC couples and individuals had participated in the gay and lesbian “baby boom” of the 1980s, but they were too few in number to support a religious school or extensive programming. Apart from holiday celebrations like Purim and Hanukkah, BCC families with children had to look to other synagogues for formal education and bar or bat mitzvah training.

During the 1990s this too began to change. A Children’s Task Force was formed in 1993. By 1995 there was a bi-monthly early Shabbat service Friday at 7:00 pm for children and families. Pool parties, camping, and other activities followed. In December 1998, Ary DeCygne-Katz, son of Naomi Katz, became the first child to have a bar mitzvah at BCC. Further expansion of services for children and their families came in BCC’s fourth decade with the establishment of the Ohr Chayim religious school.

The educational needs of BCC’s adult members were also addressed. Rabbi Edwards began her weekly Thursday night Torah study soon after coming to BCC, and it has continued ever since. BCC’s monthly bagel brunch and book discussion group began in January 1995 with Milton Steinberg’s As A Driven Leaf, and is still going strong. Rabbi Edwards and other guest teachers have taught various adult courses at BCC over the years. Some BCC members have also taught courses; Mark Levine taught a well-researched Jewish History class for more than a year in 1996-97.

In 2000 BCC began an innovative adult education program known as “Queer Jewish Think Tank.” The first courses in this program were taught by Rabbi Benay Lappe, a Conservative rabbi who had been forced to remain closeted in rabbinic school and the early part of her career. The program was sponsored by Maggie and Dave Parkhurst, who had been looking for years for a Reform temple where serious adult education could be found (unlike BCC, most other temples’ programs seemed to revolve around children and bar/bat mitzvah preparation). Rabbi Lappe introduced BCC students to the practice of Talmud study, and explored most of the passages in Torah and Talmud that have a bearing on same-sex relations or gender variant individuals. Rabbi Aaron Katz, as BCC’s scholar in residence, continued the program in 2003-04. Though formal courses ended after a few years, the Queer Jewish Think Tank still exists in cyberspace.

By the start of its fourth decade, BCC had largely completed its recovery from the challenges of the early 1990s. Rabbi Lisa Edwards and Cantorial Soloist Fran Chalin were well-established in their roles as BCC’s clergy, the AIDS epidemic was no longer decimating the membership, and programming had been initiated to serve all segments of the congregation. But we still had dreams to fulfill. During the years 2004 to 2008, BCC took great strides toward achieving many of its goals: a religious school for our children, the restoration of our survivor Torah scroll, legal marriage for same-sex couples, and the long-time dream of a new home for our beloved congregation.

The Trueman Years. In 2005 Brett Trueman was elected president of BCC. Brett had previously served five years as BCC’s treasurer, four of them while living in Northern California (and later served as treasurer and president once again). More than any other individual member, Brett spearheaded BCC’s transformation and expansion in its fourth decade, culminating in the purchase and dedication of our new building at 6090 W. Pico Blvd.

Brett’s first major act as president was the hiring of our Executive Director, Felicia Park-Rogers. Felicia came to BCC with a wealth of experience in fundraising, non-profit management, public relations, and community organizing. She had served as executive director of COLAGE (Children of Lesbians and Gays Everywhere) in San Francisco.

Rejuvenating and diversifying BCC’s spiritual life was also a high priority for Brett. This included monthly Shabbat dinners before services, Israeli dancing after, and a “guest artists” series in which rabbis, cantors, and musicians participated in occasional Shabbat services. Out of this effort grew the still-popular Ruach Chayim, a musical Shabbat evening service on the last Friday of the month. Now led by Cantor Juval Porat, Ruach Chayim initially featured student rabbis from HUC along with guest musicians.

By 2004 BCC had established an active religious school known as Ohr Chayim, an intergenerational learning program for adults and children. A children’s choir was formed, family Shabbat dinners and services expanded, and more BCC children became bar or bat mitzvah in our shul. In 2007 BCC hired an Education Director, Leah Zimmerman, and Ohr Chayim grew into a Shabbat morning school and family service meeting three times each month during the school year. BCC students could now prepare for b’nai mitzvah ceremonies in their home shul, and parents and other family members could also have a chance to participate fully (rather than dropping the kids off and picking them up later).

In 2006 Men’s Havurah chair Jerry Nodiff and Mike Halstater spearheaded a series of Shabbat services, panel discussions, and cultural events known as “Bridges to Understanding,” bringing together Jewish, Muslim, and Christian speakers for dialogue with BCC members.

Another group, led by Ray Eelsing, created a L’Chayim Legacy Circle to educate congregants about estate planning, encourage them to remember BCC in their wills, and honor those who choose to do so.

In 2007-09, student rabbi Joe Hample expanded BCC’s adult education programming with his “Evolution of Judaism” series and other innovative courses. Another student rabbi, Dr. Rachel Adler, shared with us the insights of her 40 years of leadership as a Jewish feminist scholar.

While all this new programming was being implemented, Brett also began working toward the fulfillment of BCC’s long-time dream of a new synagogue home. BCC had outgrown its facility at 6000 W. Pico Blvd. years earlier and had considered finding a new building for many years, but we had always concluded it was not financially possible. The Board engaged an outside consultant in 2006 for a feasibility study on a capital campaign for the purchase and renovation of a new building in which BCC could expand its services and programs further and grow its membership. By the beginning of 2007, BCC had exceeded all projections and expectations by raising over $2 million in pledges from some 35 individuals and couples. All members were offered the chance to participate and, with pledges and contributions ranging from the very generous lead gift by Bill Resnick to the proceeds from recycled cans and bottles collected by Melissa Irom z”l, the total eventually reached about $3.5 million. In March 2007 BCC began a series of focus groups to solicit input on a shared vision for our new home, including such questions as where it should be located, how many rooms it should contain (full kitchen, social hall, classrooms, office space, etc.), and what artistic designs it should reflect. In the meantime a search began for a suitable building.

Survivor Scrolls Reunion. On Sunday, March 20, 2005, Torah scribe Neil Yerman came to BCC from New York to assist in the restoration of a portion of our Holocaust survivor Torah that we had received on permanent loan back in 1973. The scroll had deteriorated to the point that it could not be read during services. With Mr. Yerman’s help BCC members (including some children) restored the passage from Deuteronomy 30:19 that we read on Yom Kippur: “Life and death have I set before you … that you might choose life,” as well as the passage read before Purim each year on Shabbat Zachor: “Remember what Amalek did to you on your journey, after you left Egypt…you shall blot out the memory of Amalek from under heaven. Do not forget!” (Deuteronomy 25:17-19). It was a very moving experience as each participant wrote a single letter, with Mr. Yerman guiding the quill pen.

Later that year, BCC organized a unique event that reunited our survivor Torah with other Czech Torahs in Southern California, and also with a human survivor from the Czech town of Chotebor where it originated. Stephen Sass, BCC member and president of the Jewish Historical Society of Southern California, had searched the oral testimonies of the Shoah Visual History Foundation to look for survivors from Chotebor. After some further sleuthing on the Internet, he located Olga Grilli z”l, a native of Chotebor who had traveled to England in 1939 on the last of the kindertransports that rescued Jewish children from Czechoslovakia before World War II. Olga survived the war in England but lost her entire family. Our Torah was the one her grandfather held and kissed every Shabbat, and on learning of its existence and home at BCC, Olga said it was the only tangible reminder she had of her childhood. We invited Olga to our “Etz Chayim” ceremonies on November 11-12, 2005, the anniversary of Kristallnacht, and she came with her children and grandchildren to BCC to meet the congregation and reunite with the Torah.

Approximately 400 people gathered at Leo Baeck Temple on that Saturday evening as 28 survivor Torah scrolls from around Southern California were carried in procession into the sanctuary. We also screened the HBO documentary “The Power of Good,” which told the story of the young British businessman Nicholas Winton who saved 669 Jewish children by organizing the kindertransports. Winton’s efforts were secret until many years after the war, when he was reunited with many of the people he had saved. After the film, Olga recounted her memories of her childhood in Chotebor and the experience of leaving her family and community behind in the face of the Nazi threat. Her son and granddaughter also spoke about the experience of visiting Chotebor with Olga in 1993 and about learning of her lost world as they grew up. Tears flowed all around, but there was also much joy at the long-delayed reunion. BCC member Sylvia Sukop developed a friendship with Olga, and visited her several times over the years, in New York and Florida, until Olga’s passing in 2018.

The Summer of Love. For much of BCC’s history, our struggles for acceptance focused on ending discrimination against LGBT people within Judaism (especially the Reform movement of which we have been a part since 1974), within the American legal system, and within our own families and workplaces. At the time of BCC’s founding, less than three years after the Stonewall Riots that marked the beginning of modern gay liberation, our love was still illegal and the closet door was still locked for most of us. But the pace of change was quick, at least in comparison to other civil rights movements. California repealed its “sodomy law” in 1976, and in 2003 the U.S. Supreme Court overturned the last 13 such state laws. By that time California had outlawed discrimination by sexual orientation in housing and employment, allowed two-parent adoptions by same-sex couples, and established a domestic partnership registry that gave same-sex couples many of the rights and responsibilities of marriage. Within Judaism, the Reform movement allowed the ordination of openly LGBT rabbis by 1990 and endorsed legal same-sex marriage in 1996.

But there had also been setbacks. In 1993, President Clinton’s efforts to lift the ban on gays and lesbians serving in the military had failed, and resulted in a “compromise” known as “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell” that allowed service only in the closet (though in practice thousands of GLBT servicemembers were “outed” and discharged before the policy was finally repealed in 2011). And in 1996 the so-called “Defense of Marriage Act” (DOMA) provided that if any state legalized marriages for same-sex couples, the federal government would not recognize them and other states would not be required to recognize them. A majority of states subsequently banned same-sex marriage by statute, and numerous states did so by constitutional amendment after a Massachusetts court found marriage equality to be a constitutional right in 2003.

On May 15, 2008, the California Supreme Court overturned the state’s statute declaring that “only marriage between a man and a woman is valid or recognized in California.” One month later, on June 17, California counties began issuing marriage licenses to same-sex couples. Many BCC couples spent much of that day in line at West Hollywood Park, and Rabbi Edwards married seven of them immediately afterward in one of the wedding tents. About 60 people gathered at BCC that evening for a group “wedding party” and the marriage ceremony of two good friends of BCC who had been a couple for 50 years.

Our joy was tempered by the knowledge that opponents of marriage equality were preparing an initiative for the November ballot to amend the California constitution to ban same-sex marriage. The possibility that there would only be a window of less than five months for legal marriage led to a flurry of ceremonies throughout the summer and fall. Rabbi Edwards married her beloved Tracy Moore, and she also presided over 43 other marriages of BCC couples. Several BCC couples who had married in other states or in Canada were now considered legally married in California as well. Many of these couples had been together for decades, and their unions had been consecrated in Jewish ceremonies years earlier by Rabbi Edwards or her predecessors. Now the state was finally recognizing what we all knew to be true, that these couples were spouses for life and had formed families as loving and worthy as any others.

Rabbi Lisa Edwards and Tracy Moore are legally married on July 13, 2008 by then Assembly Speaker Karen Bass (Photo: Kenna Love)

Unfortunately, a majority of the voters did not share our joy and passed the infamous Proposition 8. The California Supreme Court later declared that the marriages that had taken place before its passage remained valid but declined to overturn the amendment. In 2009 Rabbi Edwards joined other local clergy in declining to sign marriage licenses until same-gender couples could once again marry legally (though she would continue to officiate at Jewish weddings for any couples). Proposition 8 was subsequently declared unconstitutional under the U.S. Constitution by U.S. District Court Judge Vaughn Walker, with the Ninth Circuit U.S. Court of Appeals affirming. Oral argument took place on March 26, 2013 before the U.S. Supreme Court. On June 26, 2013, the Supreme Court dismissed the appeal by the Proposition 8 proponents for lack of judicial standing, thereby restoring legal same-sex marriage in California. At the same time, the Court struck down as unconstitutional section 3 of DOMA, ordering the federal government to recognize the legal same-sex marriages then allowed in 13 states and the District of Columbia. In 2015, the U.S. Supreme Court finally declared marriage equality for same-sex couples to be a constitutional right nationwide. Though it took far too long, the dream of legal same-sex marriage had become a reality.

By the middle of its fourth decade, BCC could be justifiably proud of its many accomplishments. From its humble beginnings as a lay-led shul for gay and lesbian adults who were rejected by mainstream Judaism, the first of its kind in the world, BCC had grown into a mature congregation. It had a diverse membership, dynamic and respected clergy, and varied programming to meet its members’ spiritual, social, and educational needs. It had long been integrated into the mainstream of the Reform movement and the wider Jewish community, had its own building, and had been in the forefront of the Jewish response to the AIDS crisis. Most recently it had established its Ohr Chayim religious school, celebrated legal same-sex marriage in California, and had started the process of finding a new synagogue home. Along with the arrival of our new cantor, Juval Porat, the fulfillment of this last dream marked the years leading up to BCC’s 40th anniversary in 2012.

Farewell to Fran, Wilkommen to Juval. In the spring of 2007, after 14 years as BCC’s Cantorial Soloist, Fran Chalin sent a letter to her “treasured congregants” explaining her reasons for leaving her position. She wanted a chance to slow down and refuel so that she could continue to be an agent of change for the long haul and explore other career options. On December 1, 2007, Fran’s farewell concert at Temple Emanuel in Beverly Hills, “Always in Our Hearts,” was an emotional evening of tears, laughter and song, with several cantors participating to pay tribute to her service to BCC and the Jewish community. Fran did not disappear, however; she directed the choir in 2008, celebrated with her husband Rob and BCC as her children became b’nai mitzvah in our sanctuary, and continued to make guest appearances on BCC’s bimah.

BCC’s search for a new cantor for High Holidays in 2008 drew more than twenty applications, including one from a young cantorial student in Germany named Juval Porat. BCC treasurer (later president) Bruce Maxwell had met Juval while traveling in Berlin and encouraged him to apply. Born in Israel and raised partly in Germany, Juval had studied and practiced architecture before deciding to pursue his passion for music and becoming the first cantorial student at Berlin’s Abraham Geiger College. This was a challenge, as he had to assist his teachers in designing his own course of study.

Juval’s introduction to BCC in 2008 led many of us to believe it was beshert, and we invited him back the following year after he became the first cantor invested in Germany since before World War II. In June 2010 his installation as BCC’s cantor was a joyous occasion, attended by many dignitaries including the German consul in Los Angeles. Since then Cantor Porat’s warmth and intelligence, his wry sense of humor, his enthusiasm and compassion have made him an invaluable part of the BCC community.

In addition to his duties as cantor at Shabbat and holiday services, Cantor Porat directs the BCC choir and has taught several courses. In our first two years in our new building, he organized and performed in four major concerts. On August 14, 2011, “Home: Cantors in Concert Celebrating BCC’s New Building,” featured 13 cantors and cantorial soloists from around California, solo and in ensemble. All relating to the theme of “home,” their songs were, in the words of Rabbi Lisa Edwards, in “all four of BCC’s sacred languages, English, Hebrew, Yiddish, and Broadway!” On December 3, 2011, Cantor Porat’s “Love in US” concert transformed our sanctuary into a cabaret, as he sang more than a dozen songs from different eras related to the theme of “love.” Two months later, on February 10, 2012, Cantor Porat offered a Shabbat sampling of Reform Jewish music over two centuries, with guest cantor Lance Tapper, coinciding with the first Southern California official visit of newly elected URJ President Rabbi Richard Jacobs.

On December 2, 2012, the BCC sanctuary was filled to capacity for a concert entitled “Voices: Celebrating Four Decades of Musical Artistry in the House of New Life.” This was Cantor Porat’s idea for a fitting conclusion to our 40th anniversary year, and he outdid himself in assembling a group of outstanding performers for a program representative of BCC’s musical past and present. He also concurrently released a CD, entitled “Shalem,” containing many of the songs performed during the concert.

Building and Dedicating our New Home. In 2006, BCC President Brett Trueman had spearheaded a capital campaign for the purchase of a new building. The facility at 6000 W. Pico Blvd. had served the congregation well, but with all our new programming we needed more space and better amenities like a full kitchen, a social hall separate from the sanctuary, and a library separate from Rabbi Edwards’s office.

By September 2008 BCC had entered escrow for the purchase of 6090 W. Pico and entered a new phase in its “Home for the Future” campaign. We began to interview architects and contractors for the extensive renovations that would be necessary before we could occupy the building, which had been vacant for several years. Once escrow closed in 2009, Ira Dankberg took on the enormous task of overseeing all of the design and construction work that would consume countless hours of his and other BCC members’ time during the next two years. BCC’s then Executive Director Felicia Park-Rogers immersed herself in all aspects of the project, chairing or serving on nearly every committee from fixtures and furniture to technology, all while continuing to oversee the day-to-day operations of the temple. In August 2010 BCC held a groundbreaking ceremony (“I dig BCC”) to mark the start of construction on our new home. The groundbreaking coincided with the 20th World Conference of GLBT Jews, co-sponsored by BCC at UCLA Hillel, and many of the conference participants were able to join us and share in our happy occasion.

Symbolic groundbreaking for BCC’s new building on August 15, 2010, left to right: BCC Building Committee chair Ira Dankberg, Karl Kreutziger of Howard CDM, City Councilman Herb Wesson, Rabbi Lisa Edwards, Cantor Juval Porat, BCC President Bruce Maxwell, architects Marc Schoeplein and Toni Lewis (Photo: Sylvia Sukop)

While the construction proceeded, BCC members prepared for the move with the Story Lines Project. This unique art project allowed members to engrave on copper strips a fragment of their stories about BCC and its impact on their lives. These strips would later be installed on the wall surrounding the ark in BCC’s new sanctuary. Several BCC members have also helped enhance our new home in creative ways. Davi Cheng and Jerry Hanson created beautiful new ark doors to complement the stained glass windows that would be moved from 6000 W. Pico (and which they had helped create). They also created a new ner tamid (eternal light) that would be solar powered, as would much of the rest of the building, thanks to William Korthof z”l. BCC is proud that its new home is the first synagogue in Southern California to be qualified for LEED (Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design) certification, with solar panels on the roof, insulation made from recycled blue jeans, carpet made from recycled tires, reclaimed wood, and drought-resistant native plants.

The April 10, 2011 dedication of BCC’s new temple home was one of the most moving and joyous events of our entire history. We began with a farewell to 6000 W. Pico, where we had observed so many holidays, celebrated so many simchas, and mourned so many losses. With our three Torah scrolls in the arms of BCC members, sheltered by a chuppah held up by other members, we marched the two blocks down Pico Blvd. to our new home to the accompaniment of Cantor Porat, Cantorial Emerita Fran Chalin, and the BCC band. Upon our arrival, Rabbi Edwards presided as a mezuzah was affixed to the entrance, and we proceeded inside to find that the magnificent stained glass windows and Story Lines wall had already been installed. After the Torah scrolls were carried in hakafot (circuits) around the sanctuary and placed in the new ark for the first time, a number of dignitaries from the Jewish community and city and county governments were on hand to offer their congratulations. We also heard the moving words of 94-year-old Max Webb z”l, the Polish-born Shoah survivor whose foundation sold us the building at a reduced price to help fulfill his wartime pledge to work for the continued survival and flourishing of the Jewish people. The ceremonies were rounded out with more music, including an original composition by Cantor Porat, a video montage of BCC history, Israeli dancing in our new parking lot, and of course food.

Our new building gives us more space for our expanding programs, with a larger sanctuary, offices for clergy and staff, a full kitchen, and separate social hall and bet midrash (library-classroom). In addition, the efforts of Ray Eelsing, Richard Lesse, and others have given us state of the art computers, phones, and security. With the leadership of Bracha Yael and the incubator grant she secured from the Union for Reform Judaism, we offered BCC Live, a comprehensive multimedia program by which BCC services could be live-streamed and recorded for future viewing. Weekly Torah study was also available by phone or online through the Virtual Minyan, a part of BCC Live, for those unable to attend in person.

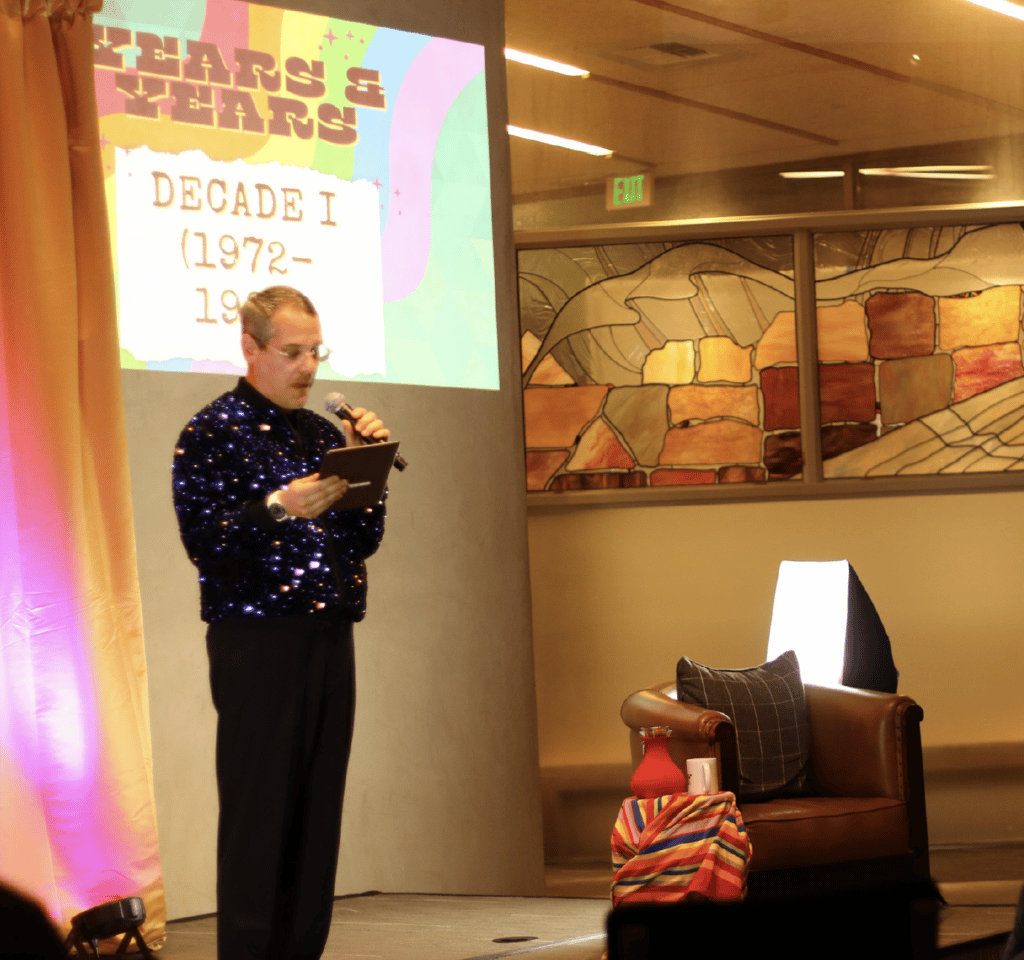

In 2012 we marked the 40th anniversary of BCC with celebrations of our accomplishments and reminders of our past, starting with a screening of the documentary “On These Shoulders We Stand,” a chronicle of the lives of 11 elder LGBT activists including our own Marsha Epstein. A gala garden party in July at the home of Dean Hansell and Cantor Porat’s “Voices” concert in December were also highlights of the year.

BCC’s three Torahs leave 6000 W. Pico under the chuppah for the procession to our new building at 6090 W. Pico,April 10, 2011 (Photo: Drew Faber)

As BCC entered its fifth decade and settled into its new home, the congregation experienced a period of relative calm. Taking advantage of the capacity of the new building to host multiple events simultaneously, BCC maintained a full calendar of programs and activities during this time. In addition to regular Shabbat services and holiday observances, BCC hosted concerts, guest speakers, an active adult education program, a religious school for children and families, and several active havurot. A few new programs began during this period, and there were some clergy and staff transitions as well.

When Rabbi Lisa Edwards retired in 2019 after 25 years as BCC’s beloved rabbi, the congregation went all out to honor her and her wife, “lezbtzn” Tracy Moore. While the search for a new settled rabbi was underway, Interim Rabbi Alyson Solomon spent a year with BCC that included the onset of the Covid-19 pandemic in 2020 along with new challenges and new opportunities for outreach beyond the Los Angeles area. Since joining BCC in July 2020, Rabbi Jillian Cameron, BCC’s new settled rabbi, has collaborated with Cantor Porat and the lay leadership in guiding the congregation through this difficult time and into the celebration of our 50th year.

Settling into our New Home at 6090 W. Pico. The versatility of our new building enabled BCC to explore new ways of serving the congregation and the wider Jewish and LGBTQIA+ community. In addition to the various offerings of BCC Live described above, a film club began in 2013 with the British classic “Sunday, Bloody Sunday” as the first screening. Thanks to the inspiration of Kenna Love, the new sanctuary was dressed up to look like a cabaret for a series of concerts in 2013-14 under the rubric of “Club 6090.” The parking lot also proved to be an asset for new programming, such as occasional outdoor services, a fully functional sukkah during Sukkot, and “Playground Sundays” athletic events beginning in 2019.

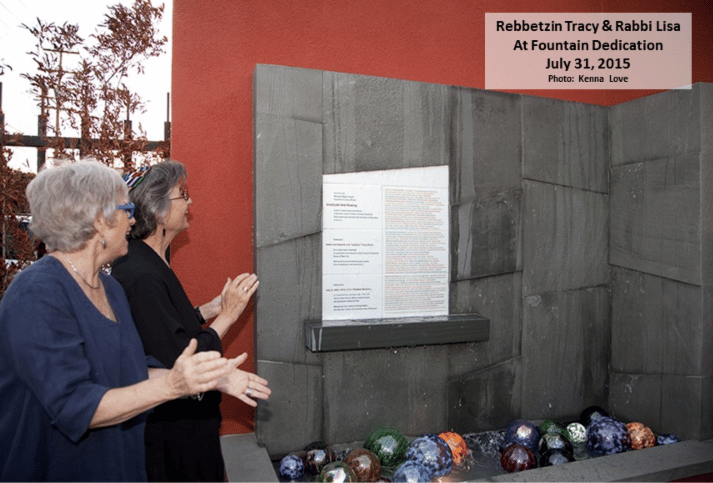

In July 2015, a fountain was built next to the Alvira Street entrance, dedicated in honor of Rabbi Lisa Edwards and Tracy Moore. Thanks to the acceleration of capital campaign contributions by generous members, BCC was able to pay off the mortgage on 6090 W. Pico in January 2017.

In the fall of 2013, Rabbi Heather Miller joined BCC as a rabbinic fellow. In 2015, Rabbi Miller became BCC’s rabbi as Rabbi Edwards became a part-time senior rabbi in preparation for her retirement. Rabbi Miller taught several courses during her time with BCC, helped revitalize our Bikur Cholim (visiting the sick) program, and participated actively in the Ohr Chayim religious school (temporarily serving as Director of Education when Leah Zimmerman stepped down in 2017). In 2018 Rabbi Miller accepted a position with another synagogue, and Rabbi Edwards returned to full-time status for her final year. One of our Ohr Chayim teachers, Rae Antonoff (now Portnoy), became Director of Education in 2018.

Felicia Park-Rogers, who had served as BCC’s first Executive Director since 2005 and played a central role in overseeing the design and construction of the new building, stepped down in 2014. She was succeeded by Ruth Geffner, then by interim Executive Director Elissa Barrett, and finally by Rabbi Jonathan Klein before the Executive Committee eliminated the position for financial reasons in 2020. Victoria Delgadillo, who had served as BCC’s office administrator or manager since 1997, retired in 2018.

The annual awards brunch underwent some changes during these years, including the addition of the Harriet Perl Tzedek Award after Harriet’s passing in 2013. In 2017, Cantor Porat, former Cantor Don Croll, Cantorial Emerita Fran Chalin, BCC members Tamara Kline and Jeanelle LaMance, and lesbian folk singer Phranc, received six “musical culture awards” for their contributions to the musical legacy that is such an important part of BCC’s identity. In 2018 the ceremony was renamed the Vision Awards.

In July 2014, BCC had its largest class of adult b’nai mitzvah, 13 in all, and in September of that year, a record 12 members opened their homes for the Great Chefs, Great Homes fundraisers. In 2017 BCC member Aviyah Farkas began reaching out to mortuaries and cemeteries to ensure that LGBT-friendly and discounted services would be available to our members.

In 2016 a vegan group began meeting, leading to the formation of a Vegan Havurah in 2019. In 2020 BCC was one of only seven U.S. synagogues to receive a “vegan challenge grant” for enhanced vegan programming. In 2022, BCC formally adopted the DefaultVeg food policy, making plant-based meals the default choice at all BCC events that include food with options for animal products to be offered as well.

As more trans and non-binary individuals began to attend BCC services, a trans havurah also formed in 2019. These new havurot supplemented the men’s, women’s, and 20s/30s (later GenX) havurot that were already active in the life of the congregation.

Rabbi Edwards’s Retirement and the Search for a New Rabbi. As Rabbi Lisa Edwards approached her retirement in 2019, the lay leadership of BCC knew that a major transition was underway. The congregation wanted to celebrate the legacy of service that Rabbi Edwards and lezbtzn Tracy Moore had given to BCC and the Jewish LGBTQIA+ community of Los Angeles. But BCC also needed to prepare for the difficult transition to a new rabbi after 25 years of the spiritual leadership of our beloved Rabbi Lisa. As early as the summer of 2018, the Board of Directors began a “listening tour” of gatherings to determine how the congregation wanted to proceed.

From March to June of 2019, a series of “nostalgic look-backs” on Friday evenings explored various aspects of BCC’s history. The topics ranged from our legacy of lay service leadership and AIDS activism to the capital campaign and building renovations for 6090 W. Pico to the “summer of love” in 2008 when Rabbi Edwards married over 40 couples. Also featured were the reunion of Czech survivor Torah scrolls in 2005, the formation of the L’Chayim Legacy Circle in 2006, and other events in which Rabbi Edwards and Tracy Moore played a role.

Rabbi Lisa Edwards and Tracy Moore receive their Vision Awards from BCC president Richard Lesse in 2019 Photo by Morgan Lieberman